Throughout the country, the Namibian Ministry of Agriculture runs farms that bolster food security on a dual track while drawing subsistence farmers into commercial agriculture.

Throughout the country, the Namibian Ministry of Agriculture runs farms that bolster food security on a dual track while drawing subsistence farmers into commercial agriculture.

Twamanguruka Nghidinwa, farm manager at Sikondo Green Scheme Irrigation Project, one of six such farms in Rundu, close to the Angolan border, explains: "We produce principally maize [corn] in summer, which is all sold to the government for the national strategic food reserves program. Maize is stored in silos scattered across the country to provide free maize meal as drought relief when needed. It's been very successful, especially during the drought of 2015."

These farms in northern Namibia, where most of the country's arable land lies, also grow vegetables grown by subsistence farmers who are interested in farming in a commercial set-up. They are invited to bid for 6 hectares (small scale farmers) and 20 hectares (medium scale farmers) in a five-year lease arrangement with the Namibian government.

Spinach and carrots on Sikondo Green Scheme Irrigation Project in Rundu, Kavango Province in northern Namibia (photos supplied)

Spinach and carrots on Sikondo Green Scheme Irrigation Project in Rundu, Kavango Province in northern Namibia (photos supplied)

Currently, Sikondo Green Scheme Irrigation Project supplies about 1,500 to 2,000 tonnes of produce to Namibia's Agromarketing Trade Agency (AMTA).

On the Green Scheme projects, farmers can grow their own choice of crops. Usually maize, wheat, vegetables (butternuts, gem squash), and watermelons on their allotment, fed by irrigation from the Kavango River. The government acts like a service provider, Twamanghuruka remarks, through placing equipment, like tractors and ploughs and inputs such as fertilizers, chemicals, and seeds at the disposal of the farmers for a usage fee. The farm managers like him, who operate the government commercial component, also act as mentors and provide guidance to the subsistence farmers.

After five years, the performance of the farmers is assessed. Twamanguruka notes that the scheme has been very helpful in letting farmers transition from livestock farming to crop production. He is a recent postgraduate in international horticulture from Leibniz University in Hannover.

Lima Kativa, agronomist and manager of the Hardap Green Scheme Irrigation Project, with Twamanguruka Nghidinwa of the Sikondo Green Scheme Irrigation project

Guaranteed loans for small-scale farmers

"To ensure that farmers have start-up capital at the beginning of each season, the government has an incentive in place that help small-scale farmers to access a loan from the agricultural bank (Agribank) guaranteed by the government," he says.

"As the commercial unit which operates the farm, we benefit from the small to medium-scale farmers as we are able to market and sell all of the produce together to local retail outlets like the OK Supermarket located in Rundu and Grootfontein. This helps us to supply produce consistently and to significantly enhance our brand."

"The Green Scheme policy intends to boost food production towards self-sufficiency and to complement the national food security strategy. It used to be supported by two state enterprises, Agribusdev and the Agromarketing Trade Agency (AMTA). However, due to a poor business model, Agribusdev was recently dissolved by the government, putting the green scheme irrigation farms back in the care of the Ministry of Agriculture."

The Green Scheme policy proposes that the vegetables and fruit produced on these farms are sold to the Agromarketing Trade Agency (AMTA), which, in turn, supplies wholesalers, caterers, hospitals, army bases, and government hostels as part of the strategy to distribute fresh produce to regions in Namibia where climatic conditions are not always suitable for vegetable production, such as Erongo, Omaheke, and Karas.

"The AMTA model has worked well for a couple of years, but it has run into a lot of challenges in terms of the supply chain and collecting data. The AMTA model has not worked as well as it was expected because subsistence farmers (who are the majority) were not trained and capacitated to transition from livestock farming to horticulture. Hence, the volume supplied annually was quite low and sometimes inconsistent," he notes. Potatoes produced in Rundu, Namibia

Potatoes produced in Rundu, Namibia

Market protectionist measures

To buffer domestic industry against imports, the Namibian Agronomic Board first ascertains supply levels of certain vegetables among Namibian producers before a retailer is granted an import permit as part of the Namibian Market Share Promotion Initiative, which was introduced almost 20 years ago with the aim of stimulating domestic vegetable production.

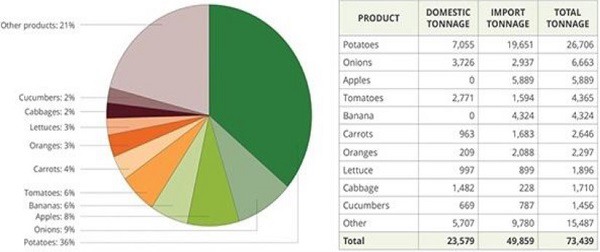

The Market Share Promotion Initiative obliges retailers and wholesalers to procure a steadily increasing percentage (32.5% in 2010) of their fresh produce within Namibia before turning to imports from, mostly, South Africa. Namibia's local and imported horticultural production in 2018 (source: Namibian Agronomic Board)

Namibia's local and imported horticultural production in 2018 (source: Namibian Agronomic Board)

"The Namibian Agronomic Board ask local producers whether they have the product, and if we do, they usually close the border to force the retailers to buy local. It has become very specific on crops we import, often in August and September, based on the data retrieved from producers and retailers."

South Africa exports significant volumes of onions and potatoes to Namibia; at the moment, the border is closed to onion imports but open to potatoes. The rest of the closures concerning other vegetables, melons, and watermelons are available here.

There are years with a deficit of product, he remarks, as well occasional oversupplies of commonly cultivated crops like cabbage (an important protein substitute in Namibia) and watermelon during November and December.

A field of Namibian onions, of which the country now produces more than it imports from South Africa

Most fertilizers and agricultural inputs arrive from Johannesburg in South Africa, a 1,780 km long journey by road that can take from two to three weeks, in turn, complicated by strict government procurement requirements.

He remarks that the cost of fertilizers really erodes their profits; the transshipment of fertilizers between the South African port of Gqeberha (Port Elizabeth) to Walvis Bay, for example, would be ideal.

Rainfed production has become very risky

"We have observed that the rain that used to arrive in October, and falling until May, now only comes in December," Twamanghuruka says; he has been at the farm since 2014, and he ascribes this to climate change.

"October has always been known as planting time for rainfed crops, but over a decade now, that has not been the case, and when the rain finally comes, it's almost like a compensation for the delay, so we find we get a lot of rain over January and February, sometimes so much that it becomes destructive and cause floods, especially in the Zambezi region."

Subsistence farmers displaced by prolonged waterlogging of their fields is becoming more frequent in the north, and It's sobering, he adds, especially as the majority of the country's farmers are subsistence farmers.

"In the past, if all households engaged in the production of, say, millet or maize, there was a sense of food security. With the current situation and the environmental degradation, we're seeing that food security from a subsistence farming perspective is not sustainable anymore."

Rainfed production has become very risky, he adds, and in the future, to ensure food security in the northern parts, the government would have to create policies to help farmers transition to semi-commercial farming, with access to loans, irrigation and machinery.

The delayed start of the rainy season is becoming a growing concern, as is the levels of water extraction from the Kavango River by Angola upstream; their northern neighbour has also been investing in its agriculture.

"Water levels have been dropping down to levels we've never experienced in the past."

For more information:

Twamanguruka Nghidinwa

Sikondo Green Scheme Irrigation Project

Tel: +26 48 1679 7015

Email: [email protected]