Saffron is a product with a high economic value that generates remarkable marketing figures in Spain. For many decades, the country has been a relevant producer of this spice, considered the most expensive in the world (not in vain, it has called the 'red gold'), although its current role in the saffron industry is much broader; in fact, it is one of the biggest players in this market.

Spain is the world's leading importer of saffron, according to data from the Economic Complexity Observatory corresponding to 2019, and the second largest global exporter of this product, behind only Iran. According to the report on saffron foreign trade published by ICEX in April 2021, in 2020 Spanish exports were worth 42.4 million Euro and imports 26.2 million. However, despite this commercial dynamism, the Spanish production, located mostly in Castile-La Mancha, shows a very different development.

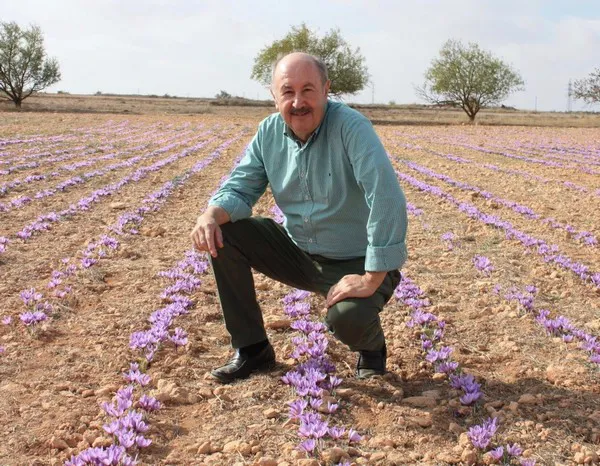

"This year's campaign is coming to an end. I believe only a few places have any product left to be harvested. It has been a shorter campaign than the previous one and, although we still have to wait until the Regulatory Council certifies the production and publishes the official figures, some producers talk about a drop of between 20 and 30%," says Francisco Martínez, from the company Azafranes Manchegos.

"The production in Castile-La Mancha has been falling for years. The yields of the plantations are not the same as before. We don't know why, although it is probably a consequence of climate change. One hectare used to yield an average of between 12 and 18 kilos of roasted saffron, depending on the area. To obtain that amount, an average of 80 pounds of roses was needed, since for every five green parts, one dry part is obtained, but now 100 are needed. Today, you are lucky if you manage to obtain 8 kilos per hectare."

"There is also more and more abandonment of farms. In this area of Albacete, in Alcalá del Júcar, quite a few producers have already given up saffron cultivation because every season they have to deal with labor shortage problems," says Francisco. "Saffron is a crop that requires a lot of dedication, because a lot is done manually, from the harvesting of the roses to the peeling and roasting. Traditionally, its production has been carried out by family businesses. All family members would help each other in the harvest. Today it is necessary to hire workers, but this is difficult, because the harvesting of saffron is very different to that of other products, such as grapes or almonds. It all depends on the flowers that are born in the field, and that cannot be predicted."

"It may happen that a crew of workers arrives in the field in the morning and there are hardly any flowers to pick, so they don't even get a full day's work that day, and that on other days there is a blanket of flowers. This makes it increasingly difficult to find people willing to work in the saffron harvest."

Data published by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food confirm this drop in the production. During the 1970's and 1980's, the registered saffron acreage stood at around 4,000 hectares and the production exceeded 40,000 kilos, and by 2009, the acreage had fallen to 143 hectares and the production was down to 1,829 kilos, according to the 2020 Statistical Yearbook. In 2017, the acreage had risen to 178 hectares, although the drop in yields - from 12.79 to 8.80 kg/ha in just 8 years - caused the production to fall to 1,567 kg. Lastly in 2019, the latest available data, shows that, although the acreage nationwide grew to 204 hectares, the production fell to 1,537 kg, with average yields of 7.53 kg/ha.

Nevertheless, saffron cultivation is still thriving in Castile-La Mancha, where it is protected under the Azafrán de La Mancha PDO quality seal. "Spanish saffron is the most appreciated worldwide, but the reality is that the production certified by the Regulatory Council last year amounted to just 450 kilos. That is why, regardless of the actual production, Spain has the reputation, and continues to be the main marketer of saffron worldwide. In fact, some 50,000 kilos are exported from Spain every year," says Francisco Martínez.

"I belong to the fifth generation of my family in the business of producing, buying and selling saffron, which dates back to 1850. I remember that, after the harvest, my grandfather would go with the saffron and scales, traveling the area of Murcia and Alicante for several months to sell it. I have continued with his activity, although in a different way," says Francisco, laughing. "We pack and market saffron mainly in the domestic market and to other exporters, although we continue selling to some customers in the United States and Arab countries, where we were exporting large quantities (on average about 300 kilos per month) a few years ago. We sell saffron with a designation of origin in the gourmet section of retailer El Corte Inglés under our brand name Karkom ('saffron' in Hebrew), the word used by King Solomon in 'The Song of Songs'. We have also launched innovative products under the Karkom brand which contain our saffron, such as honey, gin, liquor, salt and candies."

Saffron cultivation is very attractive economically. A kilo of Spanish saffron costs 4,000 Euro on average, says Francisco. "That is why the Regulatory Council should focus on the production, on providing producers with bulbs that will make it possible to achieve good yields and on helping them to prevent their giving up on this very profitable crop."

For more information:

For more information:

Francisco Martínez Navalón

Azafranes Manchegos, s.l.

Tel.: +34 967 474 093

[email protected]

www.azafranesmanchegos.com