The company Rijk Zwaan's Zaadteelt en Zaadhandel first saw the light of day in 1924 in Rotterdam. The fascinating 100-year history of this company, the world's fourth-largest breeder of fruit and vegetable seeds, is described in the book 'Moving forward together', which can be downloaded free of charge via Rijk Zwaan's website. It is an entertaining chronicle full of interesting facts, amusing anecdotes and dozens of old photos from the archives. We caught up with Manager Chain Jan Doldersum to find out more.

Excursion with cucumber growers to Enkhuizen in1926; 2nd row left Rijkent Zwaan, father of Rijk, behind Hendrik Zwaan, 2nd row right Rijk Zwaan

Excursion with cucumber growers to Enkhuizen in1926; 2nd row left Rijkent Zwaan, father of Rijk, behind Hendrik Zwaan, 2nd row right Rijk Zwaan

What have been some of the key milestones over the past hundred years?

Our story started in the 'roaring twenties' with a shop in Rotterdam called Rijk Zwaan's Zaadteelt en Zaadhandel. Less than a decade later, in 1932 to be precise, Mr Rijk Zwaan started doing his own breeding – first in Bergschenhoek and then later here in the Westland region, which is still home to our headquarters today. He not only bred open-field vegetable crops, such as cauliflower, leeks and carrots, but also crops for indoor cultivation, although there were no large greenhouses back then of course. We pioneered this market in the Netherlands for many years, including after the war.

First store: Rijk Zwaan at Zwaanshals in Rotterdam in 1926

First store: Rijk Zwaan at Zwaanshals in Rotterdam in 1926

A second milestone, after the decision to start doing our own breeding, was the internationalisation of the company from the mid-1960s onwards. Up until then, our assortment had been entirely focused on Dutch growers. The first office we opened abroad was in Welver, which is near Dortmund. In the 1980s, we also opened facilities in Spain and France, and in the 90s we moved beyond Europe – adding locations in America, India and Australia – to develop and produce vegetable seeds in opposite seasons. Europe is currently still our biggest market, but our business in the Americas is growing very fast. Especially Mexico, as a strong vegetable exporter to the US, has become very important for us. And Brazil's share of turnover is increasing all the time.

As a family-owned business, Rijk Zwaan is the odd one out among the world-leading seed companies. Has it always been family-owned?

The company's independence has been a constant through its first 100 years and this will continue to underpin the next 100 years as well. However, there was a brief interlude in 1986, just as biotechnology was emerging and there was no successor from within the family. Around that time, several multinationals, such as Shell and Unilever, were investing in large seed companies. Jaap Zwaan, the then-owner, sold Rijk Zwaan to BP Nutrition. But because the breeding business had a very long return on investment, BP decided to offer the shares for sale again just three years later. In 1989, the three board members – Anton van Doormalen, Ben Tax and Maarten Zwaan – bought back the shares in a management buyout, supported by Cebeco-Handelsraad (the Cebeco Trade Council).

Price list 1934-1935

Price list 1934-1935

This was a defining moment in the history of Rijk Zwaan, as it enabled the company to regain its independence. The Cebeco Group held 70% of the shares, and the three board members owned 10% each. In 2001, Rijk Zwaan became completely independent again when the three families bought back the remaining shares from Cebeco, thanks to financing from Rabobank. In the following year, the company issued share certificates for employees. To this day, our employees can still participate in the scheme once every three years.

What is the added value of a family-owned company in the breeding sector?

Publicly listed companies are required to report their figures every quarter, which puts the focus on short-term financial results. As a family-owned company, profit maximisation doesn't have to be our ultimate goal. After the management buyout, we formalised our core values and company culture in a document: our 'triptych'. The key goal for Rijk Zwaan is to create a healthy working environment and good working conditions for its employees. Of course we have to be profitable, but that's not our primary goal. Besides offering our people good jobs, other core values within Rijk Zwaan are honesty, reliability, long-term relationships with suppliers and customers, and respect for the environment.

Rijk Zwaan wins the very first Fruit Logistica Innovation Award in 2006

Rijk Zwaan wins the very first Fruit Logistica Innovation Award in 2006

As a family-owned company, we can also make long-term investments in new crop breeding programmes. One example of that is our move into breeding berries. That's an investment for the next 10, 20, 30 years. We don't have to recoup that investment in the next two years; we're in it for the long term. We refer to this as our 'first century' with good reason.

So Rijk Zwaan has never acquired a company?

We did acquire a company once. It was the lettuce company TS Seeds. That was an exception, because it's not easy to mix two 'blood types'; we much prefer autonomous growth. We could have opted to pursue an acquisition for our new Berries programme, because lots of small breeders are active in that market, but it suits us better to set things up ourselves. It takes longer, but we believe that it's a more future-proof approach.

Where does Rijk Zwaan stand today?

When I joined Rijk Zwaan in 1996, the company had a turnover of 50 million Dutch guilders (approx. €22.5 million), and last year it was over €600 million. After Vilmorin from France, Bayer from Germany and Syngenta which is currently Chinese-owned, we are number four in the vegetable seed world. Making up the rest of the top ten are BASF, Bejo and Enza which also both started out as Dutch family-owned companies, two Japanese breeding companies Sakata and Takii, and lastly East-West Seeds. These ten companies account for over 80% of the global vegetable seed market. Rijk Zwaan currently has 35 independent subsidiaries in 31 countries, and distributors in more than 100 countries. We provide jobs for 3,900 employees, including 1,650 in the Netherlands. We sell seeds from more than 25 crops, amounting to around 1,500 commercial varieties in total.

RetailCenter Berlin opening 2017

RetailCenter Berlin opening 2017

What are the determining factors when deciding whether to set up an independent subsidiary?

The most important factor is the overall market potential in the region in question: how many seeds could we sell? Besides the size of the market, political stability is essential. And the crops must also fit with Rijk Zwaan's portfolio. For example, South Africa could well reach a turnover of several millions. But Thailand, which is also a very large country in terms of horticulture, is not such a good fit with our predominantly western assortment. Our biggest crops are cucumbers, lettuces, peppers, tomatoes, spinach and melons. These are Western-oriented products, so there's no point in starting a subsidiary in Thailand. We still work with a distributor there.

How many breeding stations does Rijk Zwaan have? Is there one for every climate?

We have 10 R&D stations. In De Lier, we do vegetable breeding for what we call the 'warm northwest European conditions': tomatoes, cucumbers, sweet peppers and aubergines for indoor cultivation. In Fijnaart in Noord-Brabant, we breed open-field crops. Outside the Netherlands, we have breeding locations in Spain, France, Turkey, the USA, Brazil, Australia, India, Vietnam and Tanzania, among others. We need locations all over the world to select varieties for local growing conditions.

Due to the rise of water cultivation, Rijk Zwaan also has had a breeding location in Dinteloord for hydroponic leafies since 2021

Due to the rise of water cultivation, Rijk Zwaan also has had a breeding location in Dinteloord for hydroponic leafies since 2021

But am I right to assume that the seed can be produced locally, if the R&D has been done elsewhere?

The Rijk Zwaan business model comprises three phases: R&D, seed production, and seed sales. The breeding is done in the locations I just mentioned. We do some of the seed production ourselves and outsource some of it to contract growers, but all seeds we produce worldwide come to De Lier for quality control, treatment, upgrading and distribution. The control is centralised to guarantee high-quality seeds. In this context, we're opening our Seed Connect Centre in De Lier next year. It's Rijk Zwaan's biggest investment to date. The new building will significantly increase our capacity for seed processing and storage. Incidentally, protectionist measures are making it increasingly complex to decide where best to produce seeds for which end markets.

Are you pioneers in terms of technology and innovation?

In a sense, you can compare breeding to Formula 1 racing: every day, a large team is working with lots of technology to develop new varieties as quickly as possible. The time to market is very important, so we use all kinds of molecular techniques and a lot of data science to speed up the breeding process. You need to be on a strong financial footing to get involved in biotechnology. That's why we set up KeyGene together with four other breeding companies in 1988. Additionally, we do fundamental research in collaboration with multiple universities and research institutes all over the world, because you can't do it alone. Every year, we invest 30% of our revenue – so around €150 million – back into R&D.

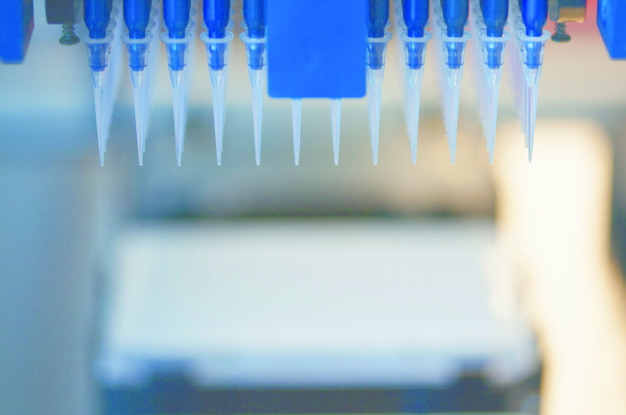

Breeding is supported by many research activities in Rijk Zwaans' laboratory in Fijnaart

Breeding is supported by many research activities in Rijk Zwaans' laboratory in Fijnaart

What do the European rules on new breeding techniques mean for your activities?

Gene editing is not yet allowed in the EU, but it is in the USA and a handful of other countries. It's faster and more precise than what we do in Europe. CRISPR-Cas is the best-known gene-editing technique. It makes it much easier to analyse or modify the function of a gene in a targeted manner.

One of the major concerns from within the European sector is that there is no level playing field, because access to genetic marker technology is still banned in the EU for now. That concern was recently raised during the ISF World Seed Congress in Rotterdam by our managing director Marco van Leeuwen, who at that time was also chair of the ISF. There are now some proposals to permit a number of techniques in the EU. However, varieties that are already being developed in the USA using the new genomic techniques can no longer be distinguished from the standard hybrid varieties sold here, because there's no way of finding out how a variety has been bred. So in effect, there is no level playing field.

Cantaloupe melon caribbean gold is the most successful variety of Rijk Zwaan

Cantaloupe melon caribbean gold is the most successful variety of Rijk Zwaan

Luckily, this is not the only path. Various technologies are available, plus CRISPR-Cas isn't the holy grail. Yes, it's a technique that can accelerate the breeding process, but you can also get a long way with marker assisted breeding, for example, which the EU does allow. This technique enables you to map genes and then see whether a certain gene with an interesting trait is passed on to the next generation, so it too speeds up the breeding process. At the same time, it remains necessary to have scientific knowledge – about plants, the genome and its relationship with the phenotype and the plant's behaviour in different crops and climates – and also market knowledge.

Looking back, what has been Rijk Zwaan's most successful product?

In terms of varieties, for the past decade that has been our Caribbean Gold melon: a Cantaloupe melon with orange flesh, a good shelf and a very consistent flavour. We sell these seeds mainly in Central America. When it comes to crops, we have a large market share with our cucumbers: from long cucumbers to snack cucumbers. We also sell a lot of those seeds in the Middle East. Our sweet pointed pepper Sweet Palermo, of which we sell multiple varieties, was recently planted on approximately 1,000 hectares in Spain. That is another product that has been doing well for years. It's better to have lasting success. Hopefully our red blocky pepper Alzamora, which is already being embraced by Dutch growers because it performs well in slightly cooler greenhouses, will extend the success curve for several more years. Additionally, we've had long-standing success with our cocktail and truss tomatoes. But these products don't even account for half of our revenue. After all, we've got more than 1,500 different varieties, including 500 in lettuce alone.

Why have you expanded into berries?

If you want to future-proof your business, you have to grow. One way to do that is to move into more countries with your existing product portfolio – which is what we do with our 35 different subsidiaries – but another way is to introduce new products onto the market. We see market potential in pumpkins, watermelons and asparagus, but also in berries. This category has grown tremendously over the past decade. But as a breeder, you have to ask yourself whether you can also offer added value in the segment in question. There aren't a lot of players in the berries segment right now. We think that we can add something.

Rijk Zwaan starts in 2024 with a new breeding location in Dinteloord for Berries - strawberries - raspberry and blackberry

Rijk Zwaan starts in 2024 with a new breeding location in Dinteloord for Berries - strawberries - raspberry and blackberry

We have set up breeding programmes for both vegetatively propagated and seed-bred varieties in strawberries, raspberries and blackberries. Strawberries can already be bred from seed, but blackberries and raspberries can't, for now. We hope to make progress in that area, because distributing seeds is a lot more appealing than distributing plant material from a phytosanitary perspective. Our focus on strawberries is also influenced by the fact that we're seeing a shift from outdoor to indoor cultivation. In the past, all strawberries came from Spain; now, they come from the Netherlands almost all year round. Indoor cultivation is growing in lots of markets, and that's a very healthy trend, including for Dutch horticulture. So it's about developing varieties for the local market.

Another shift over the past decade is that lettuce, one of your specialities, is being increasingly cultivated in hydroponic systems. What is driving this development?

Hydroponics, or growing lettuce on water, is simply a very sustainable model. You can make better and more efficient use of labour, and you have stable production all year round, which improves food security. Ultimately, it's about the stability, cleanliness and certainty with which you can grow something. But the price matters too, which is why I'm currently still a little sceptical about vertical farming. Many high-tech projects have failed in the past two years. And for now, indoor cultivation of iceberg lettuce is too cost-intensive. Nevertheless, it's possible that the pressure of soilborne diseases, water scarcity or other climate-related issues will lead to hydroponically grown iceberg lettuce in the next ten years. It could happen.

Salanova -- one cut, ready - Red butter half core cut

Salanova -- one cut, ready - Red butter half core cut

With Salanova, Rijk Zwaan was one of the first in the sector to market a lettuce concept under a consumer brand. Does the market offer scope to promote specific varieties of vegetables, as is already done with fruits such as apples, pears and mandarin oranges?

It's a complex situation because, both in Western Europe and North America, vegetables are a category that grocery retailers like to link to their private labels – and I understand that, because it's a way for supermarket chains to differentiate themselves – so they give brands very little shelf space. Nevertheless, we believe in explaining the unique flavour characteristics of a certain variety or concept. But our company doesn't have such deep pockets as the likes of Coca Cola, nor does our business model really allow us to create a real consumer brand. So we have to be inventive. The only way to do it is not only to have a product with a unique selling proposition aimed at consumers, but also to collaborate with partners. We firmly believe in what we call the 'golden triangle': the breeder, the grower and the retailer; branded products have to be introduced onto the market together with the grower and the trader or retailer. Sweet Palermo is a good example. The categories that are suitable for launching new concepts together with chain partners include fruiting vegetables, but also melons and convenience products such as bagged salads. It's more difficult for a product such as leek.

Climate change is one of the challenges in the current horticultural landscape. How is Rijk Zwaan contributing to food security?

Sustainability and climate change are two very important topics in breeding. For open-field crops, it's necessary to develop varieties that are better able to withstand hot, cold or salty conditions, for example. Meanwhile, crop cultivation is increasingly moving from outdoors to indoors in order to guarantee year-round production. One good example is lettuce. In the USA, where much of the lettuce is still grown in Salinas Valley, a lot of high-tech greenhouses have been built in the past five years, mainly for the production of the more specialised leafy crops. Climate change is forcing us to breed not only resilient varieties for open-field production, but also varieties that are suitable for the new cultivation techniques in high-tech greenhouses.

In this context, we're involved in Crop XR: a ten-year research programme financed by the National Growth Fund that will explore the impact of climate change on the development of varieties, and how resilience can be defined. We are doing this together with the partners from KeyGene and from Genetwister, another collaborative partnership of breeders.

Rijk Zwaans Development Cooperation Committee supports small-scale growers in Africa and provides training on a demonstration field in Tanzania

Rijk Zwaans Development Cooperation Committee supports small-scale growers in Africa and provides training on a demonstration field in Tanzania

Are you also looking at how food security can be defined in developing countries?

Both from a commercial angle and from a corporate social responsibility perspective, we are investigating which varieties perform well in countries that pose significant challenges in terms of their infrastructure and political context. For example, we have a breeding station in Tanzania, so we are breeding for Africa, in Africa. But we also have our own Committee for Development Cooperation that organises training for small-scale growers in Guatemala, Peru and a number of African countries, among others. It often revolves around basic techniques: how to grow a crop, how to use fertiliser, how to administer crop protection agents. Initiatives like these, as well as setting up schools for local communities, are all long-term projects.

How important is the gas price from Rijk Zwaan's perspective?

Low-energy growing is certainly a topic, but it's no longer as urgent as it was two years ago. The success of Alzamora, our market-leading blocky pepper variety, is partly due to the fact that it could be grown at one or two degrees cooler, without compromising on the number of kilos. That was actually a coincidence, because we didn't breed it specifically for that. However, it taught us that we also need to breed with reduced energy consumption – in terms of heat and light – in mind.

Successful brand concept SWEET PALERMO, now also in 4 colors sweet bell pepper

Successful brand concept SWEET PALERMO, now also in 4 colors sweet bell pepper

Which challenges do you foresee in the future?

We definitely may not forget the labour issue, in terms of both availability and affordability of labour. How can we make varieties that require less labour? Crops such as lettuces and gherkins are already harvested mechanically, plus there are all kinds of robotisation projects under way in greenhouses for crop maintenance activities and the harvesting of tomatoes, peppers and strawberries. It's not a matter of if, but when. That means you need to breed varieties that are compatible with mechanisation.

Generally speaking, another very important breeding objective is the cost efficiency of crops. This is also evident in the case of resistances, because if you introduce a ToBRFV-resistant tomato on the market that achieves 20% less productivity, for example, then you've still got a big problem. In our case, the highly resistant tomato varieties we bring to market achieve virtually the same average yield per hectare as before the ToBRFV outbreak.

Recently, customers from a number of countries can also order seeds via Rijk Zwaans' digital webshop

Recently, customers from a number of countries can also order seeds via Rijk Zwaans' digital webshop

The market complexity over the past three to five years has not only been caused by virus pressure and climate challenges. The COVID-19 pandemic and the inflation as a result of the global political instability have also had an impact on our portfolio management. There has been very little room for innovations. For example, it hasn't been easy to introduce our Tatayoyo pepper – a variety that won us the Fruit Logistica Innovation Award two years ago. Retailers preferred to keep their assortment simple, and were most focused on availability and price. Even sustainability, which is an important topic, took a back seat for a while. Luckily, things are now picking up again.

Last but not least, the sector as a whole has another huge challenge to tackle: convincing consumers to eat more fruit and vegetables. One way we do our bit is by making very active use of our LoveMySalad social media channel, and by developing all kinds of campaigns together with value chain partners. 'Moving forward together' is essential in this respect too, but we have every confidence that – together with our partners – we will be able to provide growers all over the world with high-quality fruit and vegetable seeds.

Jan Doldersum

[email protected]  Rijk Zwaan Nederland

Rijk Zwaan Nederland

www.rijkzwaan.nl

https://www.lovemysalad.com/about