For anyone involved in tomatoes, the abbreviation in this article’s title needs no explanation. Anyone growing, breeding, packaging, or trading tomatoes has to deal with this, the tomato brown rugose fruit virus (ToBRFV).

More than two and a half years after the virus was first officially discovered in the Netherlands, that much is now clear. If not because of infections in Dutch greenhouses, then because the market has been set in motion. Last summer, for example, ToBRFV infections caused tomato shortages which in turn resulted in 'winter prices'. It is expected to affect the coming season’s market too, although also energy crisis does. Plantings have been disrupted, and production will peak at unusual times.

The term ‘ToBRFV-effect’ was used for the first time last summer, at least in Dutch tomato circles. That is because this virus’ contamination rates have risen sharply, and the spread is considerable, not only in the Netherlands. The virus has been a hot topic and major cause of concern for growers and breeders for several years now. Since it was first officially found in the Netherlands in spring 2019, ToBRFV has spread rapidly worldwide. It is easily transferable, and virologists call it "highly persistent". That is reiterated by the fact that this virus can survive for long periods without a host plant in the greenhouse, on clothing, or even crates.

ToBRFV symptoms in a German greenhouse in 2018. Photo by Heike Scholz-Döbelin with Eppo.

It surfaced in Germany in 2018. But scientific articles list Israel as the first place this virus was found in 2014. The plant virus, which is what it is, is not dangerous to humans and animals. But it wreaks havoc on tomatoes, bell peppers, and chilies. It hits tomatoes the hardest, by far. That the virus is harmless to humans and animals has been continually emphasized since the first reports of it began circulating.

And a good thing, too, because once ToBRFV started becoming a serious issue in the Netherlands, it caused a panic. A virus and the consequent negative publicity can cause major financial damage. Everyone in the tomato world who experienced the Wasserbombs crisis in the 1990s is well aware of that. Because what if consumers decide to stop buying (Dutch) tomatoes out of an unwarranted fear of the virus?

Q-status

That has not happened so far. But, certainly, in 2019, people kept very quiet about the virus. So much so that in that year, several specialists from the Netherlands felt compelled to share information with the market. René van der Vlugt was one of them. "Without clarity, there’s no real action, and that’s desperately needed," he noted in July 2019. René underlined the importance of caution in reporting about viruses in greenhouse horticulture. Precisely because of trade and political interests. He, however, also stressed that since it is a persistent virus and true threat, ToBRFV should be taken seriously.

In March 2019, the first rumours of ToBRFV findings began to do the round in the Netherlands. However, it was not until October of that year that a confirmed infection was officially reported. Not long after, on November 1, 2019, the virus received European quarantine (Q) status. This means you have to report a (suspected) outbreak to the authorities. Even before it gained Q-status, the Netherlands was not in favour of such a status. That was because of the "lack of clarity" about the virus at the time. Also, "(clearing out a greenhouse) has a considerably greater impact on a tomato company than the virus itself," a Netherlands Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority (NVWA) spokesperson said in May 2019.

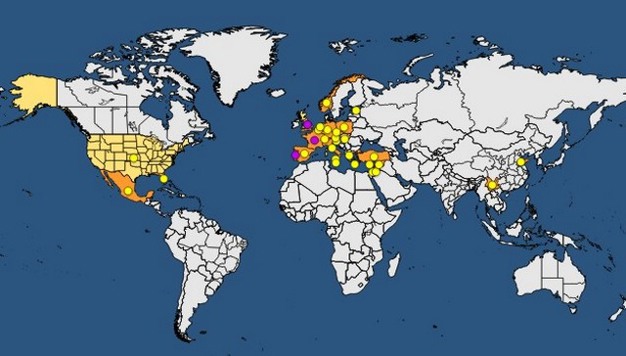

Spread of ToBRFV worldwide, as tracked by EPPO on a map

How this virus spreads has now become clearer. That is evident in the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organisation’s (EPPO) frequently-consulted virus distribution map. It is widely spread, which is why the Netherlands continues to point out the Q-status’ disadvantages. It greatly affects the Netherlands as a large, but at the same time, small player. That is in terms of the workforce when it comes to, for example, virus testing and tracing research. The Q-status is still there, despite protests from several sides, among whom were the NVWA and the National Plant Protection Organisation (NPPO) of the Netherlands. They hoped to convince the rest of the European member states that, once Q-status is ended, (strict) seed and plant material standards can halt the virus’ further spread.

ToBRFV counter

In the Netherlands, the number of ToBRFV contaminations has been steadily rising. The NVWA has been keeping a transparent count since the first official outbreak. At last count on June 2022 there were 41 infected farms in the country. The virus has been identified at a total of 57 cultivation sites since mid-2019. Growers whose crops are infected come under supervision and have to start working with a package of officially determined hygiene measures.

You cannot get rid of this virus overnight. Growers have become used to many viruses over the years, such as the tomato chlorosis virus (ToCV). But ToBRFV is proving to possibly be an even more virulent enemy. Before ToBRFV reared its head, there was a lot of to do around ToCV in 2018. There still is. Last autumn, the Dutch virus control association TuinbouwAlert pointed out that ToCV is still around; it is just latent.

Some growers have since succeeded in getting rid of ToBRFV entirely. The NVWA figures of June 2022 show that 12 locations have officially eliminated the virus. There were also two places where it cropped up again. That is despite the growers clearing the infected plants and cleaning and disinfecting the greenhouse. By now, some growers have decided to switch to other crops, like cucumber. At least six growers already did. That is because this virus is so relentless. Since discussing ToBRFV remains difficult, this is not something growers are particularly keen to advertise. However, talks are gradually becoming more open.

For instance, tomato grower Leo van der Lans has been in the media several times last year (Algemeen Dagblad, WOS). He discussed the ToBRFV infection that continues to plague his business. Leo also does not think it will be completely eradicated. "We’ll have to learn to live with it," he told WOS in September 2021. Where there have been outbreaks, growers have reported 5 to 30% harvest losses to the NVWA. They do not have to clear out their entire greenhouse. The infected plants do, however, produce less. And they must be removed from the greenhouse to prevent further spread and greater damage. Fruit that the virus has damaged is not attractive enough to sell.

Things outside the Netherlands are officially relatively quiet (too). Overseas, there are no ToBRFV counters such as the one kept by the NVWA. The Belgian Federal Agency for the Safety of the Food Chain (FAVV), for example, does not have one, at least not publicly. Not a reproach, merely an observation. The FAVV, like the NVWA and plant health services elsewhere, does share hygiene protocols. And, if asked, also contamination figures. Meanwhile, the EPPO’s infection map, even with no ToBRFV counters, has become increasingly coloured. Last year in particular, one country after another was reporting contaminations. Often these are 'first finds', but countries like Spain and the United Kingdom also report (re)new(ed) outbreaks.

Solution Along with increased infection reports, more and more reports of (new) resistant varieties have been circulating since the end of last 2020. Several (large) breeding companies are busy creating more resistance in their varieties in their laboratories and demo greenhouses. That is, however, not a simple, let alone a quick process. Breeding always takes time. Breeding companies have now gained insight into a gene that adds, as it is called in breeding language, an 'intermediate' or 'high' ToBRFV resistance to tomatoes. These kinds of genes have proved successful in combatting other tomato viruses.

Along with increased infection reports, more and more reports of (new) resistant varieties have been circulating since the end of last 2020. Several (large) breeding companies are busy creating more resistance in their varieties in their laboratories and demo greenhouses. That is, however, not a simple, let alone a quick process. Breeding always takes time. Breeding companies have now gained insight into a gene that adds, as it is called in breeding language, an 'intermediate' or 'high' ToBRFV resistance to tomatoes. These kinds of genes have proved successful in combatting other tomato viruses.

The higher the resistance, the fewer virus symptoms (discoloured leaves, spots on a tomato) a plant will show. There are varieties now being tested in many places. Breeding companies are using these to target countries such as Mexico and regions like the Middle East and the Mediterranean. A vaccine could be another 'solution'. But as long as the virus has a Q-status, producing such a vaccine is not only (virtually) impossible. It is illegal too. That was demonstrated in the Netherlands in September 2021. The NVWA raided a site where someone was allegedly attempting to develop such a vaccine.

Growers are desperate for a solution. Yet, they are realistic and expect new threats after ToBRFV is dealt with. For now, they are forced to adopt almost 'hospital-like hygiene practices at their cultivation locations. Nowadays, when you enter a tomato greenhouse, you must be covered from head to toe. You might even see a laundromat rather than tomato plants. Growers have spent a lot of money on washing machines to wash their staff's clothes.

And crates are being cleaned with even more advanced systems than ever before. This container disinfection is also a point of attention for trading and packaging companies. They use (reusable) crates. When it comes to plant viruses and, thus, ToBRFV, it is recommended to separate the container flows as much as possible. The crates should be cleaned and decontaminated before they enter the company.

Growers are buckling under all these investments, hygiene costs, and the continual threat of a ToBRFV re(contamination) with the subsequent production losses. Added to that, they are hit by the energy crisis from last autumn onwards. Electricity and gas prices have skyrocketed, causing growers to reconsider their strategies. Is it still worth switching on the lights fully when production costs are higher than the returns? The energy crisis, along with the ToBRFV situation, promises, like in 2021-2022 an extraordinary (winter) season. That is, perhaps, the only certainty at present.